|

In the car world there’s red, and then there’s red. The two might seem identical, but what you put on a Ford Fiesta isn’t necessarily the same as what you’d see on a Porsche.

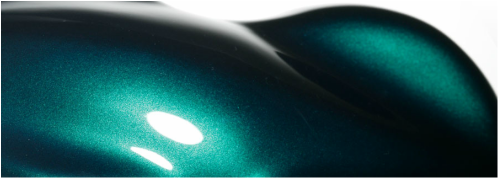

Often, the difference comes down to effects – specifically, the flakes and synthetic materials that paint makers and automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) mix into their coatings and paints. Some might glint and glitter in the sun, while others change colour depending on the angle from which they are viewed, and still more instead exhibit a subtle depth or glow. The challenge for paint companies and automotive OEMs alike is finding new materials and effects that will make heads turn, sell cars and further differentiate one vehicle from another. More than a decade ago, big paint companies such as PPG, BASF and Axalta (at the time, called DuPont) began to explore making pigments with “microscopic glass beads, recycled mirror chips, volcanic dust and flakes of processed aluminum” that would reflect light in new and interesting ways, according to a New York Times report. Other companies, such as EMD Chemicals and JDSU, discovered, designed and developed the raw flakes and materials that make such effects possible. One material in particular stood out – a then-unknown compound called Xirallic that, when mixed into paint, is responsible for the sparkle and shimmer exhibited by many of the bright, metallic colours on vehicles today. When Xirallic was released, says Luiz Vieira, vice-president of EMD Chemicals’ performance materials division, and whose company patented the compound, “consumers at that time had no idea what Xirallic was. “But over time, as the OEMs realized that these materials were helping [them] sell more cars, they started putting them on other models, other brands,” Vieira says. Ford, for example, used the pigment on certain models of the Expedition, Navigator, and F-150. Nowadays, new effect pigments are released to the market every few years. Some mimic the vibrant colours and patterns found in nature, an effect known as biomimicry. JDSU has, for a number of years, produced a colour-shifting effect called ChromaFlair that exhibits a different colour depending on the viewing angle; it can be added to the Range Rover Autobiography for $14,500. Some auto makers will even use multiple pigment and coating layers on top of one another to combine various effects. John Book, custom colour solutions product line manager at JDSU, describes one of the company’s latest effects, a biomimicry material known as Moth Eye, “because the surface of the flake is replicating that of a moth’s eye, or bug’s eye. “Once it’s applied in paint, it gives this after-glowing effect,” Book says. After five years of development, it isn’t yet on the market, but auto makers are interested. Meoxal is another new metal flake effect pigment manufactured by EMD Chemicals, and introduced at a European coatings show in 2012. It was first used on one of Renault’s 2014 models, and is advertised to radiate like desert sand. Often, these pigments appear in premium vehicles first. BMW offers several effects – “Frozen” uses silicates in a clear-coat finish for a velvety-matt surface; with “Pearl”, flakes of mica refract light over the surface, making the vehicle appear to change colour; and “Pure Metal Silver” achieves the effect of liquid in a metal state by using aluminum nanoparticles in the base coat. “The way the products typically make themselves present in the market starts with the high end,” Book says. “And, as the industry gets more familiar with the applications, and they can judge the consumer reaction, they cascade down to the more mass-market. [It’s] a very common sort of path to greater commercialization.” In some cases, the cost of a particular effect might drop with time. That’s the case with a popular three-layer or tricoat process, also known as tinted clear coats, that’s used to create especially deep reds, blues, oranges and golds. “They start with a base coat. They probably add some special effect like a Xirallic, or just aluminum, or even a ChromaFlair. And then they’ll apply a mid-coat that has a very finely ground red pigment, so it’s very transparent,” Book says. “That increases the saturation. And then finally they’ll apply the high-gloss clear coat to give it the durability and the gloss.” The price point has come down such that, according to Book, it may only cost a few hundred dollars for that colour option on a Ford Focus, for example, versus several thousand dollars in the effect’s early days. In other cases, a premium brand might use a higher concentration formulation of a particular paint on a premium product versus a lower-end model – resulting in a deeper or more saturated colour on one model over another, yet the durability of the paint remains the same for both. Sometimes, manufacturers will assume the cost of higher-end paints in lower-cost vehicles as a way to “sway consumers for your brand because of design and colours and appearance,” says Shane Dreher, EMD marketing director. “If you look at Kia Motor [or] Hyundai, some of their colours are very bright, very rich in a way. And Mazda also has very, very rich colours.” Some of the most potentially lucrative work is being done on pigments that aren’t even colours – and isn’t aimed first at the high-end. EMD unveiled a product this year called Xirallic NXT. It’s a version of the company’s popular Xirallic effect designed specifically for achromatic coatings – whites, silvers and blacks – or, about 80 per cent of automobile colours, according to EMD. You’re likely to see it on vehicles within two to four years. “White [is] one of the top three colours in the market,” Book says. ”There’s where you’re going to get your payback, right? If you’re doing black, white and silver, how can I get a new effect?” MATTHEW BRAGA Special to The Globe and Mail Published Thursday, Oct. 23 2014, 4:00 AM EDT

1 Comment

|

Archives

February 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed